Child Development Research is an umbrella organization dedicated to restoring and preserving the mental health of children, especially those who have suffered under the extreme trauma of organized persecution. This includes documenting patterns of normal child development and the disruptions, distortions, and adaptations which occur during and in the aftermath of trauma. The organization is dedicated to discovering patterns of persecution, trauma and resilience and promulgating approaches which can ameliorate the long term effects on victims of past, present, and future mass dehumanization. One of our points of focus is nonverbal expressions of normal and disrupted child development.

We work with a professional staff with the strong support of volunteers, survivors, community resources, and collaboration with other Holocaust related groups and educational organizations.

Goals:

- To develop and support projects which further normal child development and aim at prevention of childhood disorders particularly those associated with extreme trauma.

- To conduct interdisciplinary, comparative studies of child development both under “normal” and extreme conditions.

- To validate non-verbal techniques of assessment of personality and treatment of mental health disorders.

- To continue our world-wide efforts to seek out and interview those child survivors of the Nazi Holocaust and later persecutions of children who have been silent To continue to systematically analyze the patterns of persecution of children under the Nazis, to assess the adaptation of children to extreme trauma, and to understand modes of recovery in the aftermath.

- To collaborate with and train mental health professionals who are treating child survivors of trauma and their families.

- To encourage and organize creative endeavors of child survivors in the visual and performing arts, writing of poetry, literature, memoirs and public speaking.

- To compile and publish a comprehensive history of the persecution of children during the Nazi era.

- To assist educators in the teaching about the history of persecution of children during the Nazi era and other periods of child persecution.

The Issue of German Reparations after WW2

At the Yalta peace conference in 1945, the three main Allies decided that Germany would pay reparations to the Allies, not in cash, but rather in the form of transferring industrial equipment, ships, trains, investments in gold, silver, and platinum of any German institution, confiscation of all German investments abroad, forced German labor to repair damages they had wrought and to harvest crops. The lists went on and on. The Soviets annexed part of Germany, leading to the forced expulsion of over 12 million Germans. A horrendous affair. It was also decided that there would be reparations to the individual victims of the Nazis. At the Paris Peace Conference it was agreed that the other axis powers must also contribute reparations.

The first step was the distribute funds to four Allied nations who would in turn distribute these funds to victims under their domain. It would be overseen by the Inter-allied Reparations Agency.

What would be a reasonable process? In 1951 representatives from 23 international Jewish organizations developed a program to oversee and help distribute funds to compensate Jews for material losses and sufferings during the Holocaust.

Negotiations with Germany led to 95 billion dollars being set aside for survivors as indemnification. In 1952 the Israelis and Germans separately signed the Luxemburg Agreement which stated that Germany would give reparations to the state of Israel of about 450 million dollars for the cost of resettling uprooted Jewish refugees. Israel, being a newly formed state, was so impoverished itself that it used most of the funds to develop its industry. An additional 450 million dollars were given to the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference) to be distributed as direct restitution to individuals who suffered material losses. The Claims Conference is still active. While the dismantling of Germany proceeded at a rapid pace, the distribution of funds to survivors often dragged on for decades.

In the 1980’s my mother and father were traipsing around the world doing interviews with child survivors of the Holocaust – a very satisfying task they shared. Although we begged her, my mother refused to fly first class, because she was still a strong socialist and condemned class preferences. My father was not a man to go and sit in first class while his wife was sitting in economy class. Thus they traveled squashed in economy class for much of the year in the 1980’s.

At one lecture my father gave at a university in Germany, a member of the audience said, “Why must we go on condemning our mothers? I am tired of it.” My father pondered this question, how many generations of Germans need to atone for the sins of their father and mothers, and grandfathers and grandmothers, no longer alive?

My father also came to discover a niche for himself. He was aware that of the deal made with Germany after their defeat. Germany pledged reparations, and the US helped compensate by investing millions in the Marshall Plan. mM father believed that Germany for the first generation gave out reparations with good intentions. However, the Wiedergutmachung, “to make good again” was offered only in monetary terms. There was no moral wiedergutmachun, he said. He believed that by 1980 Germans were no longer self flaggelating for what they had done, but were beginning to feel victimized themselves. At one lecture my father gave at a university in Germany, a member of the audience said, “Why must we go on condemning our mothers? I am tired of it.” My father pondered this question, how many generations of Germans needed to atone for the sins of their father and mothers, and grandfathers and grandmothers, no longer alive? He came upon responses to the growing German resentment. One was that the trauma of living through the Holocaust did not stop after Germany’s defeat nor even at the death of the survivors. The trauma was passed on in many ways from generation to generation. Some children grew up feeling the guilt the surviving parent felt, a guilt sometimes for all people who are tortured and mistreated.

Some children are raised by child survivor parents who seek to reclaim their own lost childhood and come to unconsciously encourage their children to mother them. My mother offered evidence for something she called “transposition” occurring when children transpose themselves into the body of a parent, feeling that they experienced the Holocaust themselves; they may have a fear of starving or being killed. This topic is explored in the book, Generations of the Holocaust. So, if the trauma is borne for generations, shall the children of perpetrators not continue to take responsibility for at least the life time of the survivor?

My father identified a second form of continuing trauma. When Jewish organizations handled distribution of reparation funds it was far less traumatizing for applicants. For example, the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (The Claims Conference) handled claims for loss of property and suffering in camps and other trauma. However, when the deciders and distributors were Germans themselves the dispersal of funds process could be traumatizing. One problem on the Jewish side initially was that under Jewish law there is a differentiation between tainted and untainted money. Many Jews and even Isreal initially refused reparations as blood money. But there is also an expression used among Jews, “Have you murdered and also inherited?” that would support acceptance of compensation.

From the German side problems arose because of the complexity of German reparation laws. At first my father says, there seemed to be an honest attempt to offer compensation. As of 1985, some 50% of survivors were receiving a pension. The complexity of German reparation law also meant those Jews with good legal representation, especially those living in West Germany had a three times greater chance of getting reparations than others living abroad. One eighty-year old survivor in Florida was being given a pension of about $5/month. The United Restitution Organization, a legal aid society was formed in New York by Jews who had trained in German law before the war. They were very helpful.

However, over time some of the Germans officials “…got tired of having to bear the burden of the sinner,” and more and more later claims were denied. The process of denial was particularly harsh because of section 7 of the Restitution law which says, “The determination (of eligibility for compensation) shall depend on the trustworthiness of the client.” This, my father explained, puts the victim into the position of the accused. Any error, any mistake by a witness or lawyer or claimant, such as writing down a wrong age or missing a deadline, would be cause for permanent rejection. Sometimes witnesses were difficult to find.

Secondly the process of answering many detailed questions of their history was traumatic. Many of the by then elderly survivors had turned to denial and forgetting in order to cope. During interrogations they were required to remember each detail and relive the horrors. Many dropped out of the process.

But the issue that attracted my father’s attention most because of the work he and my mother did with child survivors was the fate of those who were deemed too young remember and thus were unharmed. The reasoning of the German psychiatrists was that the applicants couldn’t have trauma without having memories. Germany was therefore not liable. Whatever problems very young child survivors had in the present time could not be attached to their experiences during the Holocaust.

My German-speaking father handled their appeals. He would go to Munich, accompanying his client, and then negotiate with the Germans. In a 1982 paper he described the very problematic section 7 of the German BEG laws:

My father claimed that with the interrogations the persecution had not completely ended. With the interrogators attempting to discredit the claimant, the interrogations were a re-traumitization, a horrible experience. He was able to win a significant number of reversals on appeal which he later wrote up.. There were also cases of those who in theory were eligible at least for a one-time payment of $1500 but were disqualified. My father is cited in an article about reparations in the Atlanta Journal, 1985, regarding one particularly egregious case. A young boy witnessed the bloody killing of his parents and later his twin brother being thrown against wall at Auschwitz. He stopped talking after that. But then he went through rabbinical college in a displaced persons camp. He said that didn’t remember anything of his experiences. The German psychiatrists said that if he was well enough to graduate rabbinical school, he didn’t need reparations. My father spent a year and a half researching and discovered that this was a school that specialized in training disturbed children. They had given him a name and birthday because he could remember neither. He won his appeal. The Atlanta Journal March 31, 1985, p14-15.

Milton points out that Holland established a restitution program for Jews harmed during the Nazi occupation of their country; it is a much smaller program, but handled by a Jewish committee and not degrading to the victims. However, by offering reparations although problematic, Germany has probably avoided many acts of vengeance. In contrast, Turkey, which has never taken responsibility for the Armenian genocide it committed, has found its embassies attacked by angry children of survivors over the more than one hundred years since the slaughter of the Armenians. Still there can never be a full resolution. The younger generation of Germans may feel as though their penance should be done and survivors often feel that there can never be sufficient compensation for a genocide. War has an impact that lasts not just for years but for generations. There is no forgetting.

In the late 1990’s the Claims Conference negotiated with the Germans to give a one-time payment of about $2,500 for those born by 1928 who suffered either in camps, ghettos, hiding or Kindertransport. It covered fetuses as well. This reduced the prejudicial treatment received by child survivors. It wasn’t a lot of money, but it was a recognition of their experiences.

Non-Jews who suffered in the Holocaust have had varied experiences with reparations. After the war, no one was giving much thought to the Roma (gypsies) who had been treated much like the Jews had. Between 250,000-500,000 Roma had been crowded into ghettos, taken off to extermination camps and murdered. Germany denied survivor claims for decades after the war, claiming that Roma were persecuted for being- not Roma- a racial discrimination, but as asocials and criminals. Roma survivors and scholars began protesting and finally in 1982, the Federal Compensation Act was amended by West Germany to include compensation for Roma. It was a victory, even though it was too little and too late. In 2012, Berlin erected a monument recognizing the genocide against the Roma.

The Poles have also sought compensation for the millions of Poles killed by Germany and the vast destruction that took place in Poland. Germany has argued that a sum was given to eastern bloc countries through the Soviets and that Poland signed a waiver of further compensation in 1953. Poles pointed out that it was the communist government, allied to the Soviets, who signed and this waiver thus did not come from authentic Polish leadership. In 2000, the Polish government received $906 million in compensation for surviving slave laborers. Few are still alive.

For many it is not about the money but about recognition of the sins committed against them. I remember once asking my father, was he happy. “Happy?” he said, “I don’t know about that. I don’t remember that feeling. I guess I am content. I have had opportunities to do fulfilling things in my life, I love my family, but I can’t claim to actually be happy.” That was sad for me to hear. When my mother had a blood clot in her lungs, my father said that if she died, he would die too. I was hurt by that, by his easy willingness to leave us, but I recognize that it was my mother who was his daily partner, not his children. When he was dying of colon cancer, he asked my mother if she would come with him. I guess she could have said yes, but she was always straight about things and declined. She carried on with her work until she could no longer do so. Their lives were so much about their work that she could carry on, lonely, but fulfilling a mission. It is a good to feel that your life was worthwhile.

Even though my parents were not technically survivors, they too, were traumatized and I imagine my nightmares as a child came to me from their fears and distresses. I wish they had created a label for people like themselves, who were not survivors or children of survivors, but children of non-survivors, children of the too early dead. Their trauma must be recognized as well. And it too is passed on.

The Last Witness: The Child Survivor of the Holocaust

Judith S. Kestenberg, M.D., and Ira Brenner, M.D.;

Read the Introduction

The Last Witness : The Child Survivor of the Holocaust; Judith S. Kestenberg, Ira Brenner; Hardcover; Published by American Psychiatric Press, Publication date: May 1996.

Preface

I recently visited the Holocaust Memorial in Miami and witnessed a powerful exchange between two men of vastly different cultures. Most of the visitors had left for the day, and a silent emptiness was descending upon the grounds. There, in the waning moments of daylight, the huge sculpture of a tattooed arm, reaching for the heavens, cast an eerie reflection in the surrounding pool. One of the last tourists, a Hispanic man, was hurrying through, explaining the significance of the photographs and maps to his son. They paused in front of a photograph of a barracks in a concentration camp, which showed the emaciated prisoners with shaven heads in their striped uniforms, locked in their cage like bunk beds. A man with a European accent was standing by the photographs also, pointing to the same scene, and sadly, but matter-of-factly, he stated to his own family, “I was there.” The Hispanic man immediately spun around, his mouth dropping open as he confronted the silver-haired man, and asked incredulously, “You were there? You really were there? Did you know Elie Wiesel?”

The European man, seemingly unfazed by the stranger’s curiosity and forthrightness, simply replied that yes indeed, he was there, but no, he never met Elie Wiesel. Still astonished and apparently not convinced, the man searched for words in English and asked many questions. Still unconvinced, he finally asked, “You have the numbers?” The survivor nodded, silently raising his forearm to show the man and his son.

The Hispanic man gasped and started to cross himself, exclaiming, “Dios mio! Dios mio!” He yelled for the rest of his family, urging them to come see this man – it was very, very important. He stood in awe, and whispered, “Worse than the holy wars!” He then asked more questions, which the survivor patiently answered. He became visibly shaken, and in the end all he could mutter was “Then it really happened.”

This dramatic encounter illustrates the challenge of meaningfully describing the Holocaust and putting it in any kind of perspective. The questioner was obviously knowledgeable, caring, and interested in the history of the Holocaust, but it did not become real to him until he had living proof. His proof came in the form of a man with “numbers” – an eyewitness. But he still could not comprehend it and compared it to the holy wars. His historical perspective seemed to remove it from the modern twentieth century and cloak it with a religious aura. He became overwhelmed and had a profound experience when his extended conversation with the survivor finally broke through his denial. It became so important for both men to communicate about the reality of horror that they struggled to overcome the language barrier between them.

The upsurge of nationalistic strivings and ancient ethnic hatreds associated with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the “ethnic cleansing” in Bosnia, and the deadly tribal war between Tutsis and Hutus in Rwanda are just a few of the many instances of mass violence today in which genocidal aggression shows itself.

This tendency toward denial in the face of an overwhelming reality can be exploited by perpetrators who count on general incredulity at reports of their misdeeds–whether incest or the Holocaust. In addition, the feelings of shame and guilt that are mobilized during victimization may keep those who have experienced trauma from speaking up. Survivors of the Holocaust, however, whose numbers are ever dwindling, have clearly recognized the crucial importance of sharing and documenting their experiences. We hope that this volume becomes a suitable forum for their voices, while at the same time broadening our understanding of the psychological aspects of survival.

As the reader will note, we offer no photographs, tables, graphs, maps, blueprints of the gas chambers, copies of incriminating Nazi documents, or extensive statistics. Such information is available, and with access to the archives in the former Soviet Union, more data will certainly emerge to add to the already enormous amount of historical evidence. What we offer is an in-depth study of the traumatic effects of genocidal persecution on the child’s psychic structure and on development throughout the life cycle. Although this book is essentially about the victims in one particular instance of genocidethough one that has become almost paradigmatic – we suspect that some of our findings will be replicated in other situations.

The upsurge of nationalistic strivings and ancient ethnic hatreds associated with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the “ethnic cleansing” in Bosnia, and the deadly tribal war between Tutsis and Hutus in Rwanda are just a few of the many instances of mass violence today in which genocidal aggression shows itself. The advent of psychodynamic sophistication in the realm of international conflict resolution has brought hope, however, that through understanding the psychology of neighbors and having an appreciation of national unresolved mourning, groups can work out their differences (see the work of Vamik Volkan, especially Volkan 1988). The signing of an agreement between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization finally to recognize each other can be seen as a very positive step in that direction.

It has been more than fifty years now since the liberation of the concentration camps and the hiding places, so we have been able to see some of the long-term effects of trauma on child survivors and their offspring. For those whose suffering persists, help is available through support groups in the various survivor organizations and through professional channels. We hope that our contribution will help mental health professionals be more aware of some of the issues confronting these patients, whose lives have been touched by the flames of the Holocaust. We may be able to alleviate some of the pain of the survivors, but the memory of those who perished endures. It endures as a somber reminder that the future of humankind hangs in the balance between the forces of creation and the forces of destruction.

…I preferred not to think of it as “giving up” each time Judy Kestenberg, whose tireless energy, inspiration, and absolute commitment to intellectual integrity, spurred me on

As a participant in this project, I have learned a great deal and am deeply appreciative of Dr. Kestenberg’s wisdom and support. However, I have lost count of the number of times, over the last ten years, that I have considered ending my involvement in this overwhelming project. After all, I was quite busy with the demands of my practice, my psychoanalytic training, my teaching, and of course my personal life. I further rationalized that I did not think of myself as a researcher and had not originally envisioned my career as taking this direction. So I preferred not to think of it as “giving up” each time Judy Kestenberg, whose tireless energy, inspiration, and absolute commitment to intellectual integrity, spurred me on: “We were invited to present a paper at….” or “Can you write a paper for…?” or “Can you speak on a panel at…?” So I kept going, pushing myself a little more, to get another interview, to present one more time, to “survive” in the project just a little longer. I quickly realized how hard it was to set ordinary limits on my time when it came to this extraordinary group of people, many of whom had pushed themselves beyond imagination in order actually to survive from one day to the next. The emotions stirred up in me each time I listened to their stories were profound and utterly exhausting. It is little wonder that for several decades after the war the world did not want to hear about the suffering of the survivors. And now “the children,” many of whom are in their fifties and sixties, have long since come of age and have needed to be heard from also. They have much to teach us, and I was compelled to listen.

When Dr. Kestenberg felt that we needed to reach more psychiatrists with our findings, I responded. With the encouragement of my friend the prolific writer Salman Akhtar, I contacted the publishing arm of the American Psychiatric Association with the idea. Much to my pleasure, it was eagerly accepted. The result is this book, a tribute to all of the last witnesses of this all too human tragedy. It could not have been put together without the expert secretarial efforts of Lorraine Amato-Margasak and Ellen Young, as well as the loving support of Roberta Brenner, whose own endurance was put to the test on more than one occasion.

This volume consists of previously published articles and new material. Although the book is a collaboration, Judith Kestenberg is primarily responsible for Chapters 1, 2, 5, and 9, and I take authorial responsibility for Chapters 4, 6, and 8. Janet Kestenberg Amighi assisted in writing Chapter 1, Chapter 3 is a joint effort by Judith Kestenberg and me, and Chapter 7 was written by Judith and Milton Kestenberg.

Chapter 2 combines two presentations. The first is a contribution to a panel, “The Psychological Impact of Being Hidden as a Child,” held at the Meetings of the Hidden Child, May 26, 1991, New York, NY, chair Dr. Sarah Moskovitz. The second was read at the Nürnberg-Erlangen Meeting on Persecuted Children and Children of the Persecuted, October 18, 1991, and was published in German in 1994 by Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht.

Chapter 3 is reprinted in revised form from an article in the International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, published in 1986.

Chapter 4 is reprinted in revised form from an article in the Psychoanalytic Review, published in 1988.

Chapter 9 is translated in revised form from an article published in German, “Kinder unter dem Joch des Nationalsozialismus,” in Jahrbuch der Psychoanalyse, in 1992. It also appeared in shortened English versions in the British Journal of Psychotherapy in 1992 and in Mind and Human Interaction in 1990.

Ira Brenner, M.D.

Milton and Judith Kestenberg:

Mr. Kestenberg was the founder and president of Kenton Associates, a real-estate management firm in Manhattan. The properties he managed included Knickerbocker Village, the Apthorp Building and Astor Court, all in Manhattan.

He was born in Lodz, Poland. After studying law at the University of Vilna and in Warsaw, he began working as a lawyer in Cracow. He ended up in the United States by chance. On a bet that he could get a visitor’s visa, he applied and succeeded. He came to the World’s Fair in New York City in 1939, but his return was barred when World War II broke out. He studied at St. John’s University in Queens and began his career anew.

After the war, in which his mother and brother died at Treblinka, he represented survivors in the German courts, seeking restoration of property and reparations. He specialized in helping children, many of them too young to remember the details normally required for legal evidence.

He was particularly concerned about the psychological impact of the Holocaust. He and his wife, a psychoanalyst who had also left Poland before the war, founded the International Study of Organized Persecution of Children in the Holocaust and traveled worldwide collecting hundreds of interviews. They also created the Association of Children Survivors to help them cope.

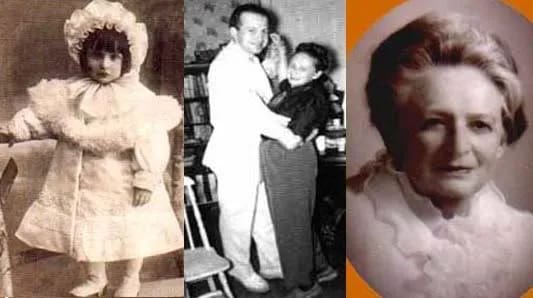

Judith Kestenberg

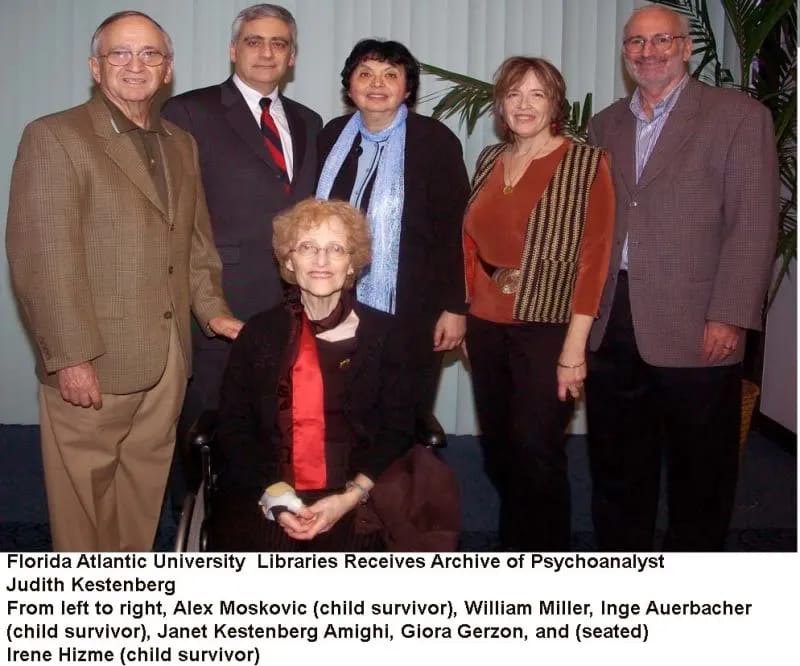

Dr. Kestenberg headed Child Development Research, which she founded 30 years ago, and Holocaust Child Survivor Studies, both based in Sands Point. With her husband, Milton, she started the research center’s International Study of the Organized Persecution of Children.

She and her associates traveled all over the world to collect taped interviews with more than 1,500 child survivors of the Holocaust and their children, as well as the children of Nazis. Fluent in French, German and Polish, she wrote two German books used to teach German children about the Holocaust.

Judith Silberpfennig was born in Tarnov, Poland, and trained in medicine, neurology and psychiatry in Vienna. She came to New York in 1937 and completed her training at Bellevue Hospital and the New York Psychological Institute.

Her husband was born in Lodz, Poland, and became a lawyer there before coming to the United States in 1939. He managed real estate in New York and, after World War II, sued in German courts to seek compensation for Holocaust victims and also organized aid for their children.

They were married in the mid-1940’s and became a team in their Holocaust pursuits when he started representing the victims, especially children, before the courts and found that many of them had only vague memories of their ordeals.

Dr. Kestenberg, a professor emeritus at New York University Medical School, taught generations of psychiatrists, psychologists, psychoanalysts and other experts on development, mental health and dance-movement therapy. She also was on the staff and faculty at Long Island Jewish Hospital.

She published seven books and some 150 professional articles. Most recently she edited, with Dr. Charlotte Kahn, ”Children Surviving Persecution: An International Study of Trauma and Healing” (Greenwood, 1998).

Her other books in print include ”Sexuality, Body Movement and the Rhythms of Development” (Aronson, 1995); with Dr. Ira Brenner, ”The Last Witness: The Child Survivor of the Holocaust” (American Psychiatric Press, 1996), and, as editor with Dr. Eva Fogelman, ”Children During the Nazi Reign: Psychological Perspective on the Interview Process” (Greenwood, 1994). Milton Kestenberg died in 1991. Dr. Kestenberg is survived by a son, Howard, of Foxborough, Mass.; a daughter, Janet Kestenberg of West Chester, Pa., and four grandchildren. Her work at Child Development Research is being continued by Dr. Fogelman and associates.